FDA Panel Narrowly Backs Dostarlimab Trial Plans in Rectal Cancer

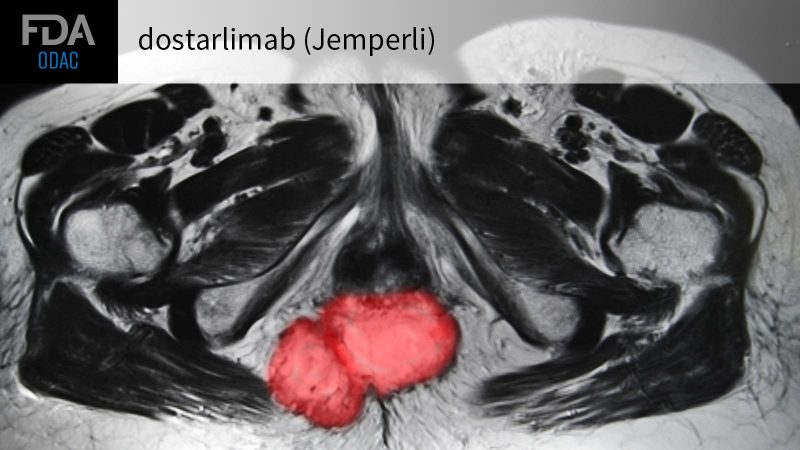

While expressing reservations, an advisory committee to the FDA backed clinical development plans for dostarlimab (Jemperli) in untreated locally advanced rectal cancer patients whose tumors are mismatch repair-deficient or carry high microsatellite instability (dMMR/MSI-high).

By a vote of 8-5, the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) on Thursday said a proposed single-arm multicenter trial from drugmaker GSK was sufficient to support an accelerated approval of the PD-1 inhibitor in this patient population. Dostarlimab is currently approved for dMMR endometrial cancer.

Initial reports of 100{c754d8f4a6af077a182a96e5a5e47e38ce50ff83c235579d09299c097124e52d} complete response (CR) rates with dostarlimab in dMMR rectal cancer “generated enthusiasm and caution, in equal measure,” said FDA’s Lola Fashoyin-Aje, MD, MPH, of the Office of Oncologic Diseases.

Those varying emotions were evident as ODAC members explained their votes.

“This agent has great safety, has efficacy, has a pretty impressive clinical complete response with the current data,” said ODAC chair Jorge Garcia, MD, of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, who was a ‘no’ vote. “However, I do not believe the data that we have — and the data that has been proposed by the applicant — is sufficient to characterize the benefits and risk in the curative setting for this patient population.”

FDA reviewers told panelists they were concerned that plans to use single-arm trials and a primary endpoint of clinical CR at 12 months were insufficient to demonstrate the drug’s benefits and risks.

However, those concerns were not enough to dissuade the majority of committee members from giving GSK’s trial plans their qualified support.

“I don’t think a randomized trial is feasible given the presentation of the existing data and patients’ overall goals and expectations,” said Christopher Lieu, MD, of the University of Colorado Cancer Center in Aurora.

“I do have some concerns about the use of complete clinical response at 12 months as the definitive endpoint, mainly because I don’t think there is a clear correlation — although there is a suggestion — of complete clinical response and disease-free survival and distant-metastasis rate,” said Lieu. “Disease-free survival at 3 years, which is a secondary endpoint of the study, will be critically important just to show that correlation.”

GSK is proposing to evaluate dostarlimab via two single-arm trials — the ongoing single-center Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) trial that has enrolled a total of 30 patients, and a proposed multicenter trial that will enroll 100 patients.

Patients in both trials will receive dostarlimab 500 mg intravenously (IV) every 3 weeks for 9 cycles and will evaluate the clinical CR rate at 12 months as the primary endpoint.

Results from the MSKCC study’s first 12 evaluable patients, presented last year at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting by Andrea Cercek, MD, and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed a 100{c754d8f4a6af077a182a96e5a5e47e38ce50ff83c235579d09299c097124e52d} CR rate at a median follow-up of 6.8 months.

In an update of the results at the ODAC meeting, Cercek noted that the first 18 patients enrolled in the study achieved a clinical CR with dostarlimab monotherapy, and that the first 10 patients have sustained that clinical CR out to 18 months.

“While the short term-benefits appear significant, we need long-term data with additional patients to demonstrate the durability of results and to better understand our ability to successfully retreat in the event the cancer reappears,” she said. “This underscores the importance of the proposed GSK study.”

A High Bar for Accelerated Approval

Standard treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer consists of multimodal therapy that combines fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy or short-course radiotherapy, and surgery.

However, according to the FDA reviewers, while administered with curative intent, the treatment is associated with short- and long-term toxicities that adversely impact quality of life, leading to the growing interest in nonoperative management of this disease.

During the course of the meeting, Lieu asked about the use of accelerated approval in a curative setting.

“When we think about accelerated approval, we’ve seen these approvals in regard to overall response rate, and that’s been in the metastatic setting, and obviously the corollary here would be complete clinical response,” said Lieu. “Where’s the bar in terms of what the FDA would like to see?”

“Obviously it has to be higher,” said Richard Pazdur, MD, director of FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence. “It doesn’t preclude the use of accelerated approval, because this is a serious and life-threatening disease, but the uncertainty is more acceptable when you’re dealing with patients in a single-arm trial who have no other therapies available to them, and that is a common scenario where we are using accelerated approval in the metastatic disease setting, where patients have gone through the available therapies.”

“So there should be greater scrutiny here, and that is why we are bringing this proposal to this committee,” he added.

Single-Arm Studies and Endpoint Concerns

Sponsor GSK argued that with dostarlimab’s efficacy well-known in the dMMR population, patients and physicians alike may be reluctant to participate in a randomized study where patients could be randomized to standard of care.

However, Sandra Casak, MD, of FDA’s Gastrointestinal Cancers Team, noted that the agency generally requires randomized controlled trials to support approvals in the curative setting “where a comparative assessment to standard of care can be performed, and endpoints of clinical benefit, such as survival, can be evaluated.”

Yet, almost without exception, panel members agreed with GSK that a randomized trial would be impractical.

The rate of response to dostarlimab “is incredibly high,” said panelist George Chang, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who was a ‘yes’ vote. “If it’s not 100{c754d8f4a6af077a182a96e5a5e47e38ce50ff83c235579d09299c097124e52d}, it’s pretty darn close to 100{c754d8f4a6af077a182a96e5a5e47e38ce50ff83c235579d09299c097124e52d}, and for a primary endpoint of clinical complete response, it’s very hard to see the rationale for a randomized design because there is no other treatment we have that can achieve a complete clinical response rate even close to that.”

“If there was ever a study where it was appropriate to do a single-arm trial, this would be it,” Chang added.

As for the use of clinical CR at 12 months as a primary endpoint, Casak said that analyses of long-term survival outcomes, such as event-free and overall survival, are “uninterpretable in the absence of concurrent controls,” and that associations between CR and long-term endpoints rely mostly on non-randomized, retrospective trials, “with marked heterogeneity that limits interpretation of data from these trials.”

Most panel members shared those reservations.

“I have a little bit of a concern with the 12-month endpoint,” said Ravi A. Madan, MD, of the NIH in Bethesda, Maryland, who voted ‘yes’ in support of the proposed trial plan. “This data is immature, and we still don’t know what happens 3 or 4 years down the road in an otherwise curable population. I think the follow-up is going to be the key and that will be the ultimate justification to validate whatever shorter endpoints will be used.”

Pamela Kunz, MD, of Yale School of Medicine and Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, also voted ‘yes’ and said that while she is supportive of clinical CR as an acceptable primary endpoint, secondary endpoints should be expanded and include those such as organ preservation rates and quality-of-life measures.

The FDA is not bound by advisory committee decisions but usually follows their recommendations.