Do probiotic supplements effectively boost your gut microbiome with ‘good’ bacteria?

The probiotics that fill supermarket shelves come in all shapes and sizes.

Most promise general digestive and immune support, but some claim more targeted treatments for people with an irritable bowel or low mood.

They’re based on the premise that a diversity of “good” bacteria in your gut improves your overall health.

And while we know this is true, there’s limited evidence that probiotics that come in a bottle achieve this.

But there is work underway to make these supplements more effective for everything from Crohn’s disease to major depressive disorder.

Your gut is full of bugs

There are somewhere between 300 and 500 species of bacteria living in your gastrointestinal tract.

And there’s lots of them, with your gut harbouring roughly the same number of microbes as there are human cells in your body. Sometimes even more.

Loading…

But don’t be alarmed.

“They do lots and lots of good things for us,” says Georgina Hold from the Microbiome Research Centre at the University of New South Wales.

“And also, changes in the gut microbiome have been identified in a number of diseases or health issues.”

Not only do your resident microbes help you digest and absorb nutrients, they also influence your immune system, your levels of inflammation and might even affect your behaviour.

The microbiome is in constant contact with the immune system. In fact, up to 80 per cent of your immune cells are present in the gut.

Through this immune system contact, different microbes can cause inflammation, which can lead to conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and cancer, or help dampen it.

When the balance is off

The consensus among researchers and clinicians is that a healthy gut microbiome is a diverse gut microbiome. The more types of bugs the better.

There’s a lot that can influence the make-up of your microbiome: what you eat, the illnesses you’ve had, the medications you’ve been on, where you live and even the pets you live with.

“The amount of physical activity we do, the levels of stress that we have in our lives, all of these factors have a huge influence on the microbes that associate with our bodies,” Professor Hold says.

Antibiotics in particular can disrupt your microbiome balance, so this is a situation where you might be advised to take a supplement.

There is some evidence probiotics containing specific bacterial species can prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea.

But numerous studies have found they are much less effective at restoring microbiome diversity after a round of antibiotics. In fact, there’s some evidence that probiotics can delay recovery.

Changing the food you eat is one of the fastest ways to influence the diversity of your microbiome.

And, as Professor Hold says, “diet is something tangible that people can have some influence over”.

Fermented foods like yoghurt, sauerkraut, kimchi and kombucha contain a decent dose of microorganisms.

But generally, a varied, plant-based diet is recommended for a healthy gut. The more diverse the food, the more diverse the bugs.

Professor Hold says when it comes to the microorganisms living in our gut, “they are what we eat”.

“If we choose to eat a vegetarian diet or a high-fat diet or a low-fibre diet, the microbes directly feed off that,” she says.

“If they’re not happy, they’re either going to behave differently or they’re going to die.”

But this food-first approach, while proven, is less targeted than therapeutics.

Faecal transplants are used in cases of serious illness, and are effective at restoring gut microbiome diversity fast, but aren’t a cost effective (or pleasant) strategy for everyone.

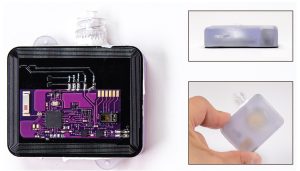

Which is why there’s still work underway to isolate the most promising and beneficial types of bacteria, encapsulate them and deliver them easily and effectively.

The future of probiotics

Probiotics aren’t just a tool to diversify the gut microbiome.

They can detect and treat disease. They can decontaminate surfaces. There’s even work underway to create probiotic-based vaccines.

“I think the future is pretty bright,” says Gustavo De Cerqueira, who works in synthetic biology at the University of Sydney. He’s also the CEO of a start-up called BiomeMega, which derives omega-3 fatty acids from bacteria.

While Dr Cerqueira is excited by the potential uses of new probiotics, he admits there are hurdles to overcome.

“It’s a process to actually bring new probiotics to market and assign those probiotics to certain functions,” he says, “and to actually demonstrate that they’re going to work in a personalised way.”

Dr Cerqueira says more clinical trials are needed to establish both the function of probiotic strains in the gut, and to prove this function is consistent from person to person.

“It’s important to make sure that probiotics are right for you, whether it’s a standalone species or the right combination of species that suits your microbiome, your genes.”

Wolfgang Marx, researcher at the Food and Mood Centre at Deakin University, says this is an important consideration.

“My gut microbiome probably looks very different to your gut microbiome,” Dr Marx says.

“So strains that are most effective to help manage depression for me, might be very different for you.”

The gut and the brain are connected through a complex network of nerves and hormones. The brain can influence what happens in your digestive tract, and the gut can influence your feelings and cognition.

Because of this connection, probiotics are a burgeoning area of research in mental health.

Probiotics are already used as an adjunctive mental health treatment in some cases, including in major depressive disorder, where small studies have seen promising results.

But, much like psychiatric drugs, probiotics aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution.

So, Dr Marx says, the field is moving towards a more personalised approach.

“[In the future] we may use an analysis of your gut microbiome to guide treatment,” he says. “As opposed to right now, where it’s just the ‘kitchen sink’ approach.”

This tailored approach could end up being a personally formulated probiotic in a capsule. Or it could be a prescription diet that nudges your gut microbiome in the right direction.

“I think it’s all on the table at the moment,” Dr Marx says.

Professor Hold agrees that while the concept behind over-the-counter probiotics is strong, the execution isn’t quite there yet.

“I think eventually we will develop probiotic combinations based on an individual person’s needs,” she says.

But there’s “an awful lot of work to do” before these personalised approaches can be taken.

Professor Hold also cautions against services popping up that promise to profile your microbiome in exchange for advice.

“If someone’s going to write a report that says, based on your microbiome profile you shouldn’t be eating sausages on Tuesdays … there is, in my opinion, no basis to that.”

Professor Hold points out that your gut microbiome changes daily — likely multiple times a day, depending on what you eat throughout the day.

And so, while the field is working towards some exciting goals, Professor Hold says “we’ve got to manage expectations”.

Listen to Dr Norman Swan and Tegan Taylor’s probiotic deep-dive on RN’s What’s That Rash? And subscribe to the podcast for more.

Get the latest health news and information from across the ABC.