When popular podcast Life Uncut posted an episode on toxic shock syndrome, it shone a light on the risk of medical misinformation

If you’ve used tampons in your lifetime, you will no doubt be familiar with the term: toxic shock syndrome (TSS).

You probably glanced at the leaflet that rolled out of the tampon box, alongside the confusing diagrams and small text.

It felt like something to fear, but did many of us really understand what it was?

The reality is that while TSS is a serious and potentially fatal bacterial infection, the risk of developing it is incredibly rare.

In Australia, exact figures are unknown, because TSS does not need to be reported.

But data from the US — where TSS cases are notified — and the UK (where reporting is voluntary), suggests the condition occurs in fewer than one in a million people, according to Deborah Bateson from the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney.

It’s thought that the rarity of instances is down to changes in tampon manufacturing methods and a greater awareness of safe tampon use.

TSS has recently found its way back into the spotlight and you may have heard it was linked to supposed chemicals inside a tampon.

You may be alarmed. And you wouldn’t be alone.

Incorrect claims about TSS

Popular Australian podcast Life Uncut, hosted by media personalities Brittany Hockley and Laura Byrne, recently promoted an episode interviewing US model Lauren Wasser — a well-known survivor of TSS.

In 2012 at the age of 24, Wasser fell ill with TSS. In a matter of hours, she went from suffering a fever and flu-like symptoms to lying in an induced coma in hospital with organ failure and minutes from death.

Loading Instagram content

Wasser survived. But she suffered life-altering consequences: both of her legs were amputated.

In the Life Uncut episode, Wasser implied her TSS was caused because tampons are “full of bleach, dioxin and chlorine” and “sprayed with pesticides”.

She added that “those toxins get into the bloodstream”, and then “start acting like the flu and start shutting down your organs. It’s dangerous”.

These false claims prompted outrage from audience members and medical professionals, including UK-based content creator Michael Mrozinski, who uses his social media platforms to debunk medical misinformation.

“I’m actually really disappointed … it’s misinformation and it’s dangerous,” Dr Mrozinski told his audience.

Professor Bateson says the important thing to remember is that TSS is not associated with chemicals like bleach, as Wasser alleged in her interview.

“We know that’s not the case … TSS is the body’s response to toxins which are produced by common bacteria found on the skin.”

The video from the podcast promoting Wasser’s interview was posted on Instagram and TikTok, clocking up millions of views. It was later removed following complaints.

The episode itself was archived, edited, and re-posted with the disclaimer that it had “been reviewed and approved by two medical doctors registered in NSW”.

Following the fallout, the podcasters released a statement thanking their audience for their feedback, and correcting the medically inaccurate statement from Wasser.

The incident reflected misconceptions surrounding TSS, and the importance of correcting medical misinformation quickly.

So, what is TSS?

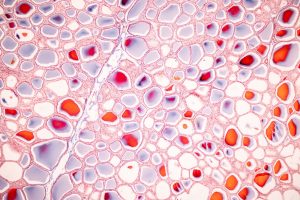

TSS is an illness that occurs in the body when toxins are produced by staphylococcus aureus (staph), or — more rarely — group A streptococci (strep).

It was first discovered in 1978 among children, and then gained prominence in the 80s and 90s when it was connected to tampon use during menstruation.

The important element to remember in this history was the release of Rely tampons in the US in 1978, with free samples given to millions of women.

The product, with an ill-fated tagline – ‘It even absorbs the worry!’ – was made of super-absorbent polyester foam and carboxymethylcellulose gel.

Alongside the changes in vaginal pH level during menstruation, the tampon created an ideal environment for bacteria to grow.

At its peak, the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported in 1980 that there were 890 cases of TSS, and 812 of those were associated with menstruation.

Sadly, in 1980 the CDC also reported that 38 women with menstrual TSS died.

They reported that the Rely tampons were associated with the spike in TSS cases, more than any other tampon product, resulting in its recall in September 1980.

Once the Rely tampons were recalled, the rates of TSS fell dramatically, and by 1989 there were no deaths associated with menstrual TSS recorded.

Be alert, not alarmed

While using tampons can increase the risk of TSS, it’s important to know that the risk remains low, and tampons aren’t the only risk factor.

TSS can affect anyone, and risk factors include skin wounds or burns, surgery, viral infections or even intravenous drug use.

It is also connected to the use of a contraceptive diaphragm during menstruation or the use of a menstrual cup — but again, complications such as TSS from using these products are rare.

As Professor Bateson explains, while TSS is rare it remains a potentially fatal condition.

“I think the key thing when talking about TSS is to be aware, not alarmed.”

She reiterates that there are a range of “perfect conditions” for the growth of bacteria which could lead to TSS in humans, and tampon use is one of those rare risk factors.

“So you’ve got this overgrowth of bacteria and then an overwhelming release of these TSS toxins in the body and an uncontrolled inflammatory response,” she says.

The initial symptoms can be small, and include a rash, swelling, redness of the tongue and throat, and peeling skin.

The importance of a fact check

Personal stories are compelling ways to raise awareness of issues and health-related topics — like the risk of TSS.

Wasser’s story is highly emotive, an element that Doctor Clare Southerton, a lecturer in digital technology and pedagogy at La Trobe University, says makes it so compelling.

“She was sharing something that really connected with the audience, which is why the video went viral,” she says, adding that for many people social media is perceived as a safe space to research information.

“We know young people in particular, especially when it comes to things like sexual health and menstruation which remains a taboo topic, tend to prefer to get health information from online sources and not necessarily from their teachers, parents, or even healthcare providers.”

While great strides have been made when it comes to female-related health issues, medical misinformation can have a very real impact on women’s lives if not corrected, says Dr Bateson.

“It’s perfectly OK to engage with someone’s content, who is speaking from a personal perspective, and balance that with a fact-check of that information,” she says.

Editor’s note 08/06/2024: An earlier version of this story said 772 women had died with TSS in 1980. The correct statistic is that out of 722 women with menstrual TSS, 38 died. This has been corrected.

Posted , updated