How psychedelic drugs alter the brain

August 13, 2024

At a Glance

- Researchers found that psilocybin temporarily disrupts a brain network involved in creating a person’s sense of self.

- The findings help explain the neurobiology of psychedelic experiences and give insight into harnessing the potential therapeutic effects of psychedelic drugs.

Psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin cause acute changes in how people perceive time, space, and the self. In ongoing experimental research, a single psilocybin dose under controlled conditions is showing promise for relieving mental health symptoms such as depression. These therapeutic effects can last long after the acute effects of the drug wear off. But it’s not clear how these drugs affect the workings of the brain and lead to the drugs’ therapeutic effects.

A research team led by Dr. Joshua Siegel at Washington University in St. Louis used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to track changes in brain activity related to use of psilocybin. Seven healthy young adults participated in the study, which involved regular fMRI sessions before, during, and after a carefully controlled dose of psilocybin. Results of the study, which was funded in part by NIH, appeared in Nature on July 17, 2024.

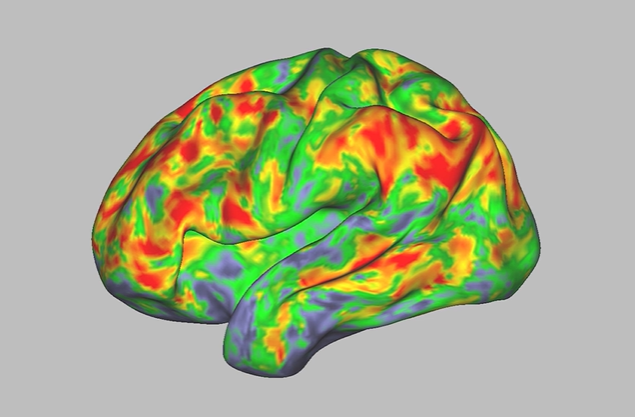

Psilocybin caused major changes in functional connectivity, or FC—a measure of how activity in different regions of the brain is correlated—throughout the brain. These regions included most of the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, and cerebellum. The changes were more than 3 times greater than those caused by a control compound, methylphenidate (a stimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). Psilocybin induced the largest changes in areas involved in the default mode network. This network is usually most active when the brain isn’t focused on a specific task. It is thought to govern people’s sense of space, time, and self.

Study participants also completed a questionnaire designed to measure the intensity of their subjective psychedelic experience. The questionnaire scores correlated with FC changes in their brains. The greater the FC changes, the more intense the person’s psychedelic experience.

Psilocybin caused activity within brain networks to become less synchronized. It also led to less distinction between brain networks that normally show distinct activity. Notably, the psilocybin-associated FC changes were reduced when participants performed a task that involved concentrating on matching spoken words with images.

Most brain activity returned to normal within days of taking psilocybin. But a reduction in FC between the default mode network and part of the hippocampus lasted for at least three weeks. This may reflect lasting changes in hippocampus circuits involved with the perception of self.

The findings shed light on how psychedelic drugs may affect brain function and alter perceptions of self. “The idea is that you’re taking this system that’s fundamental to the brain’s ability to think about the self in relation to the world, and you’re totally desynchronizing it temporarily,” Siegel explains.

This research provides important information to inform scientists as they seek to harness these drugs’ therapeutic potential. However, the researchers strongly caution against self-medicating with psilocybin, as there are serious risks to taking it without supervision by trained mental health experts.

—by Brian Doctrow, Ph.D.

Related Links

References: Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain. Siegel JS, Subramanian S, Perry D, Kay BP, Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Reneau TR, Metcalf NV, Chacko RV, Gratton C, Horan C, Krimmel SR, Shimony JS, Schweiger JA, Wong DF, Bender DA, Scheidter KM, Whiting FI, Padawer-Curry JA, Shinohara RT, Chen Y, Moser J, Yacoub E, Nelson SM, Vizioli L, Fair DA, Lenze EJ, Carhart-Harris R, Raison CL, Raichle ME, Snyder AZ, Nicol GE, Dosenbach NUF. Nature. 2024 Jul 17. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07624-5. Online ahead of print. PMID: 39020167.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); Washington University in St. Louis’s Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research, McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience, Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center, Hope Center for Neurological Disorders, and Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology; Dysphonia International; Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute; Kiwanis International.