Colonial Foundation Diagnostics Centre to use ‘spatial biology’ to speed up inflammatory disease diagnoses

Denise McFarlane used to work as a massage therapist and even treated Stevie Wonder backstage before one of his concerts in Melbourne in 2008.

“He did tell me that I got him through his world tour,” the Bendigo woman said.

“He sang me a song about having a massage with Denise in Melbourne, so I had a lot of enjoyable moments and fun times backstage.”

Stevie Wonder gave a signed drum skin to Ms McFarlane’s son. (Supplied: Denise McFarlane)

However, those fun times gradually stopped after she started to experience “incredible” regular pains.

“I was trying to knock it over with Panadol and anti-inflammatories and nothing was seeming to do anything,” she said.

During this time, Ms McFarlane moved to Bendigo and continued to regularly see doctors who would prescribe stronger medications on each visit.

“I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t move. I didn’t know what was going on,” she said.

“This was when it culminated to debilitating pain.”

After four years, Ms McFarlane was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in 2020.

“By the time I was diagnosed I couldn’t get in or out of a car if I needed to get somewhere,” she said.

It took Ms McFarlane four years to be diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. (ABC Central Victoria: Philippe Perez)

Boosting medical research

Researchers in Melbourne hope a new centre will provide quicker diagnoses for people suffering inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis through “spatial biology”.

The $21 million Colonial Foundation Diagnostics Centre is philanthropically funded and will work as a partnership between the Walter and Eliza Hall Research Institute and the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

It is hoped that the research could eventually help Ms McFarlane and more patients like her.

Professor Marie-Liesse Labat says spatial biology could give an accurate diagnosis for a range of diseases. (Supplied: WEHI)

Professor Marie-Liesse Labat from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) of Medical Research, said spatial biology was a new field of science that looked at how different cells and molecules were arranged within an organ in the body.

“So you could think of an analogy — like an organ is like an ecosystem — where each cell would be a tree, a plant or an animal,” Professor Labat said.

“If you can imagine in an ecosystem, it’s like you’re looking at a tree or flower completely independently of its own surroundings. It looks really weird and doesn’t give us a whole context of information.

“But now we can study these plants or animals … how they are organised, where they are located and importantly how they communicate with each other.”

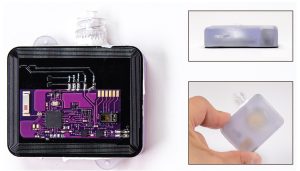

Merscope machines will help researchers study communications among cell types. (Supplied: WEHI)

Professor Labat said spatial biology meant she could see how cells worked together and better understand how diseases progressed.

“That’s really the big game changer for us,” she said.

While the centre does not yet have a specific physical location, researchers will have access to WEHI buildings and use patient data samples from the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Focusing on several diseases

As well as rheumatoid arthritis, researchers will initially focus on diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, lupus and also allergic conditions.

A spatial biology tool will aim to visualise millions of gene products with cell types, colour-coded for deeper tissue exploration. (Supplied: WEHI)

“We’re starting off by focusing on an area of enormous need and strength within our clinical and research environments, which is immune and inflammatory disease,” WEHI director Professor Ken Smith said.

“There are 80 or more such described diseases that about 10 per cent of the population will suffer from at some point in their lives.

“If you add allergy in that list, that goes to 30 to 40 per cent of the population.”

Royal Melbourne Hospital chief executive Shelley Dolan said she hoped the new technology would benefit patients.

“The Colonial Foundation Diagnostics Centre will enable our teams to gather in-depth information from the blood tests and biopsies we perform on patients, allowing us to better understand their disease and provide improved personalised care,” Professor Dolan said.

Life after diagnosis

Ms McFarlane said while life was much better since being diagnosed, she still had to drive more than an hour to Sunbury, a satellite suburb of Melbourne, to see a specialist.

Ms McFarlane still has to travel for treatment. (ABC Central Victoria: Philippe Perez)

She said she was hopeful spatial biology could help with her treatment in the years ahead and prevent others from the long and painful diagnosis period she experienced.

“If people are having unknown symptoms that keeps bothering them … just put your hand up,” she said.

“With the new diagnostic tools that are coming on board, it doesn’t hurt to get tested, particularly if you have a family history.”

Since her diagnosis, Ms McFarlane has trained as a nurse and now works in mental health.

Her hands will no longer allow her to work as a massage therapist.

“I do mourn the loss of doing it [massage] but I’m really grateful I got the opportunity,” she said.