Sleep-tracking devices are wiring the world for the study of sleep. What will we find?

When a powerful earthquake hit New South Wales early one morning this month, causing seismic waves to ripple through Sydney’s sandstone bedrock, data scientists in Sweden detected a disturbance in another realm: sleep.

An above-average number of people in the surrounding area briefly woke at the time of the quake, as plates rattled in cupboards and dogs barked in protest, according to data gathered by a popular Swedish-made sleep-tracking app, Sleep Cycle.

Sleep-tracking has boomed in popularity worldwide, giving researchers access to millions of hours of sleep data and transforming our understanding of how to improve our sleep, and in turn how sleep affects our health.

When a natural disaster hits or a COVID variant spreads, or when Christmas approaches or daylight savings begins, researchers can now see widespread changes in sleep and health metrics at the scale of a city or a country.

“We can look at a huge chunk of the world now,” Michael Gradisar, Sleep Cycle’s head of science, says.

“Sleep is one of the first things to go wrong in a person’s health. Sleep is the canary in the mine.”

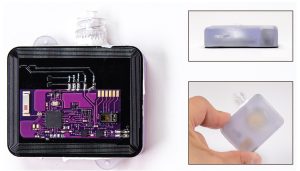

Sleep-tracking apps like AutoSleep (pictured) quantify sleep quality and duration. (Supplied: AutoSleep)

Less than 10 years since the first sleep-tracking Apple Watch, the world is wired for the study of sleep.

How did we get here? And what might we learn?

Our story begins in 2015, with a Sydney computer scientist.

Sleep study goes from the lab to the bedroom

“I’m one of those people that dive into things and learn about them and get obsessed,” says David Walsh, recalling how he built the first-ever Apple Watch sleep-tracking app.

“I just read tonnes and tonnes of scientific papers … Everything under the sun.”

David Walsh, here at home in Sydney, updates AutoSleep with every Apple Watch hardware improvement. (Supplied: David Walsh)

The 57-year-old is largely unknown in Australia outside developer circles, but he played a crucial role in the global story of the rise of consumer sleep tech.

Apple released its first smart watch in 2015 without its own sleep-tracking app. Mr Walsh spent months studying the science of sleep to develop an Apple Watch app that inferred when the wearer was sleeping based on movement and heart rate data.

Testing his creation, he observed how small changes in behaviour had an exaggerated affect on the amount of time he slept each night, at least according to the app. An after-work beer could shave hours off sleep-time.

“It just makes you very, very aware of the consequences and what you’re doing to yourself.”

Sleep is crucial to good health, but humans are generally bad at assessing how well they’re doing it. You can count calories or time runs to improve nutrition and exercise, but, until recently, tracking sleep meant a night in a lab, swaddled in electrodes.

AutoSleep was released in early 2016. Eight years later, the paid app has more than 5 million users, Mr Walsh says.

“China is a very big market for us.”

Initial scepticism turns to excitement

Scientists like Gabriel Pires, a sleep researcher in Brazil, met the arrival of AutoSleep and other consumer sleep-tech with caution.

“We started posting papers saying, ‘Be careful with these new technologies, they don’t work well.'”

Mike Gradisar, then a professor of sleep science at Flinders University, was also sceptical.

“I remained a critic of wearables up until COVID,” he says.

The first wearables weren’t capable of accurately tracking sleep, Mike Gradisar says. (Supplied)

During the pandemic sales of devices like smart watches grew as people with disposable income turned to technology to optimise their health and fitness.

Investment followed, and the accuracy of some devices improved. Apple, for instance, beefed up its smart watch, adding sensors to track the electrical activity of the heart, as well as blood oxygen content and body temperature.

“Everything flourished during the pandemic because of commercial reasons. The market was so big,” Dr Pires says.

Dr Gradisar jumped from the university to the private sector, taking a job with Sleep Cycle, a Swedish company that makes a sleep-tracking smartphone app that, among other things, records coughing and snoring. He was excited to study the data generated by Sleep Cycle’s 2 million active nightly users.

“The potential was just like, ‘Wow’.”

As he joined Sleep Cycle, the Omicron variant was spreading through New York. A persistent dry cough was a commonly reported symptom of the virus.

Sleep Cycle’s data scientists wondered if their user data showed a correlation between the increase in night-time coughing in New York and the increase in Omicron cases.

“We saw approximately one week before confirmed cases of Omicron an increase in night-time coughing as a population,” Dr Gradisar recalls.

“It’s almost like it’s an early warning system. We had all of these phones at night collecting information.”

Some consumer tech can now diagnose sleep disorders

In early 2024 Samsung’s smart watch’s sleep apnoea detection system received approval from the US health regulator following an eight-month review. It was the first consumer smart watch to clear this hurdle and proof the line between the best wearables and clinical sleep tech was blurring.

Sleep apnoea, a disorder that can lead to heart problems and depression, may affect as many as a billion people worldwide, but is under-diagnosed.

The conventional method of diagnosis requires a night in a sleep lab, which is inconvenient and often expensive. While Samsung says its feature is not meant to replace a sleep clinic, the regulatory approval means millions of people have access to a test that can detect sleep apnoea without the need for a medical professional.

Apple’s smart watch, the most popular in the world, received the same regulatory approval earlier this month.

Danny Eckert, director of the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University, believes consumer sleep tech could ultimately be better at diagnosing sleep apnoea.

A polysomnography at a sleep clinic remains the gold standard for diagnosing sleep disorders. (Getty: FG Trade)

A 2022 study co-authored by Professor Eckert found up to half of single-night diagnostic studies for sleep apnoea, which is the current gold standard, misclassify severity.

“The single-night tests are hugely noisy and inaccurate,” he says.

“We’ve never been able to monitor accurately what’s going on with sleep apnoea in the home. Now we can do it every single night for weeks, months and years.”

The rise of ‘million-hour’ sleep studies

In-home monitoring has opened the door to a new kind of “big data” approach to studying sleep.

Such studies use millions of hours of data gathered from consumer wearables to test the variables affecting sleep quality, and how sleep affects mental and physical health.

Variables might include caffeine intake, exercise, daylight savings, international travel across time zones, work schedule, time of year, or the state of the weather.

“You can answer any kind of question where there’s an independent variable captured by big data,” Greg Roach, a professor of sleep research at Central Queensland University (CQU), says.

“The whole world is becoming a sleep laboratory.”

The results can be surprising. Smart watch data (shared with Sleep Cycle) shows users’ baseline heart rate increases in the weeks leading up to Christmas, Dr Gradisar says.

“People are maybe not only stressed, but they’re drinking more and more and more.”

A 2023 study, co-authored by Professor Eckert, used in-home data on sleep duration and blood pressure from almost 13,000 adults over nine months to demonstrate that high night-to-night variability in the severity of sleep apnoea is associated with high blood pressure.

“There’s something about the higher variability that’s bad for the body that we didn’t even know about before,” Professor Eckert says.

“The technology has allowed us to see things of clinical importance that we had no idea about before because we just couldn’t measure them.”

But every techno-utopia has its dark side. Jen Walsh, director of the Centre for Sleep Science at the University of Western Australia, sees a future where sleep data is requested by employers or insurers, as proof of health or performance.

“The data is going to be used against us at some point,” Dr Walsh says.

“Is your employer going to insist you get seven hours sleep?”

Selling the perfect night’s sleep

Sleep is now a big business. As money flows, the grifters follow.

Many sleep scientists embrace the potential of sleep tech, but are worried about where it’s heading.

“The good technologies are diluted among a sea of poor ones,” Dr Pires says.

“And what do these poor technologies want? They want to fool you.”

Many wearables claim to track sleep cycles, such as REM or deep sleep. According to multiple recent studies, they’re often wrong.

A 2022 study by researchers at CQU found six common wearables correctly assessed REM and deep sleep two-thirds to half of the time, compared to the results of the gold-standard method used by sleep clinics.

Charli Sargent, a co-author of the paper and senior research fellow at CQU, says wearables “need a bit of improvement.”

“I think we’re only at the stage of using these devices to track the timing of sleep.”

For about $900 you can buy a “sleep companion” that can sense and mirror your breathing. (Supplied: Somnox)

Professor Eckert agrees.

“It’s very difficult to measure deep sleep and these sorts of things without an electrode.”

He fears sleep will go the way of nutrition, where the market is flooded with products making unverified claims.

Like weight loss or gut health, sleep sells. The sleep tech market is worth billions, stuffed with mattresses that adjust their firmness, spine-aligning body pillows, weighted blankets and eye masks, lights that brighten in the morning to mimic a sunrise, soothing scented sprays, and pajama “lounge pants”.

For more than $4,000 you can buy a sleep-tracking subscription-based mattress that adjusts its temperature and comes with an endorsement from Elon Musk.

“Sleep tech has to be done with scientific oversight, rather than just flogging off devices for the sake of making a buck,” Professor Eckerts says.

Products are hitting the market faster than regulators or scientists can review them, Dr Pires says.

“I really follow this literature. I cannot know every sleep technology or every sleep app. No-one can do that.”

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has a members-only review of the quality and reliability of new and popular sleep devices. National health regulators, such as Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration, maintain online registers of products proven to have a therapeutic benefit.

But, as with many “health” products, most sleep tech avoids the scrutiny of regulators.

Ten years ago, the sleep science profession broadly dismissed the scientific potential of consumer sleep-tracking.

Now, the sleep tech industry appears to be growing out of control, and the billion-dollar business juggernaut has no regard for the patient, cautious work of sleep scientists.

“If we don’t tackle this situation with science … we will lose track of it,” Dr Pires says.

“Sleep tech will become purely commercial.”

Loading