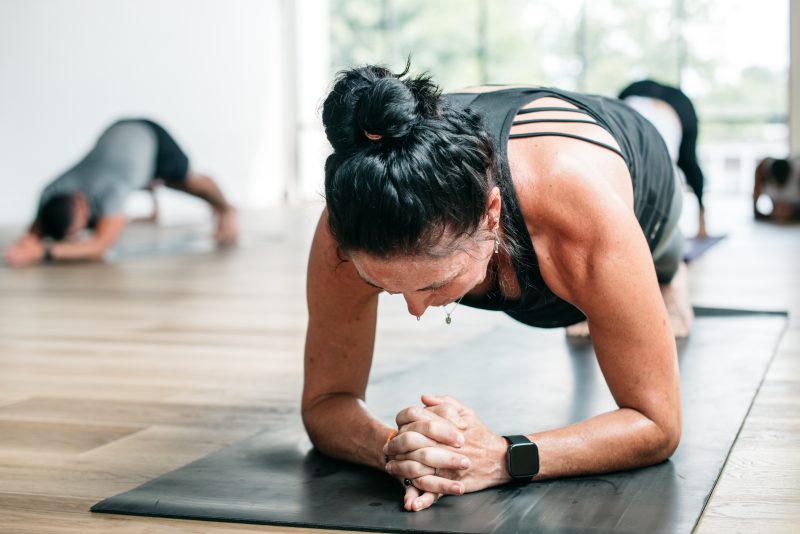

Hot yoga may help relieve depression symptoms

At a Glance

- In a small study of people with moderate to severe depression, hot yoga reduced symptoms in half the participants.

- Larger studies to compare hot yoga to other treatments for depression are needed.

Depression—a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in most activities for at least two weeks—can be debilitating. Every year, more than 8% of adults in the U.S. experience major depression. The condition can affect people of all ages, races, ethnicities, and genders.

Antidepressant medications can help some people with depression feel better. But they don’t work for everyone. Some also may not be able to tolerate their side effects, which can include weight gain, sleep disturbances, and fatigue. Psychotherapy can provide relief from depression but may be difficult to access. Alternative approaches to relieving the symptoms of depression are badly needed.

Small studies have suggested that yoga—which combines physical activity with mind-body awareness—may hold promise for treating depression. Preliminary research has also suggested that heating the body, a process called whole body hyperthermia, may provide some relief of depression symptoms.

In a new NIH-funded pilot study, a research team led by Dr. Maren Nyer from Massachusetts General Hospital looked at a combination of yoga and heat, or hot yoga. Hot yoga sessions are done in a hot (105°F) room. The researchers assessed whether people with major depression would be able to adhere to regular hot yoga practice for eight weeks. They also looked at the potential effects of hot yoga on depression symptoms. Their results were published on October 23, 2023, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The team recruited 80 people (82% women, 31% non-White) with moderate to severe depression from the surrounding community. Participants were allowed to continue any treatment they had already started, including antidepressants, during the study.

After an initial assessment, the participants were randomly assigned to either at least two sessions of hot yoga per week for eight weeks, or to a waitlist that served as the control group. (The control group was offered hot yoga sessions after their eight-week waitlist period had completed.) Depression symptoms before, during, and after the study were scored using a well-established method.

Demographics like age, gender, and the use of additional treatments did not differ between the two groups. Thirty-three people in the hot yoga group completed at least one yoga session and were included in the analysis. However, only 12 people in the hot yoga group (36%) attended 12 or more classes. Thirty-two people in the control group participated in at least one follow-up assessment.

At the end of the eight weeks, 16 people in the hot yoga group had their depression scores drop by more than half, indicating a substantial reduction in depression. Only two people in the control group experienced a similar reduction in depression symptoms. Twelve of the people in the hot yoga group had their scores drop low enough to be considered in remission from depression, compared to two in the control group.

These improvements were seen even though people in the yoga group attended, on average, just over one class a week compared with the minimum of two prescribed.

“We are currently developing new studies with the goal of determining the specific contributions of each element—heat and yoga—to the clinical effects we have observed in depression,” Nyer says.

Larger clinical trials are also needed to compare hot yoga to other active treatments for depression. And more research is required to understand which groups of people with depression might benefit the most from such a physically rigorous intervention.

—by Sharon Reynolds

References: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Community-Delivered Heated Hatha Yoga for Moderate-to-Severe Depression. Nyer MB, Hopkins LB, Nagaswami M, Norton R, Streeter CC, Hoeppner BB, Sorensen CEC, Uebelacker L, Koontz J, Foster S, Dording C, Giollabhui NM, Yeung A, Fisher LB, Cusin C, Jain FA, Pedrelli P, Ding GA, Mason AE, Cassano P, Mehta DH, Sauder C, Raison CL, Miller KK, Fava M, Mischoulon D. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023 Oct 23;84(6):22m14621. doi: 10.4088/JCP.22m14621. PMID: 37883245.

Funding: NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).