‘Low-intensity’ blood stem cell transplants for sickle cell appear safe for lung health

News Release

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

NIH study finds lung function remained stable or improved in adults after transplant.

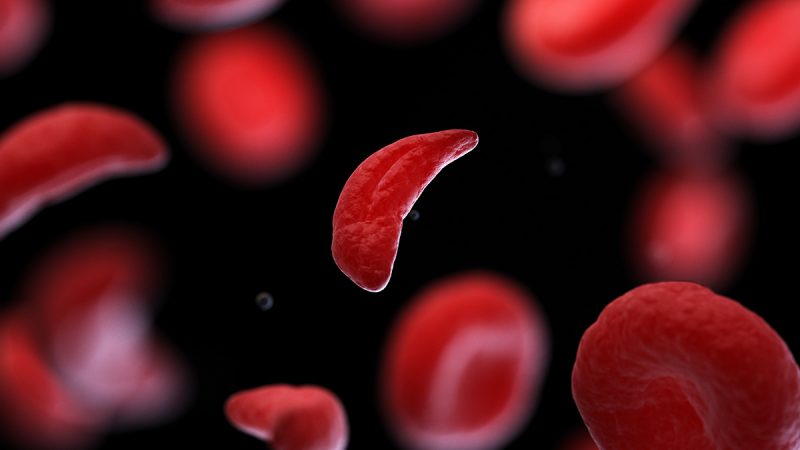

So-called low-intensity blood stem cell transplants, which use milder conditioning agents than standard stem cell transplants, do not appear to damage the lungs and may help improve lung function in some patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to a three-year study of adults who underwent the procedure at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Damage to lung tissue and worsened lung function is a major complication and leading cause of death in people with sickle cell disease, a debilitating blood disorder. The new study, published today in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society, helps answer whether less intensive types of transplants, which tend to be better tolerated by many adults, by themselves either cause or promote further harm to the lungs.

“By using a low-intensity blood stem cell transplant for sickle cell disease, we may be able to stop the cycle of lung injury and prevent continued damage,” said study lead Parker Ruhl, M.D., an associate research physician and pulmonologist at NIH. “Without the ongoing injury, it’s possible that healing of lung tissue might occur, and this finding should help reassure adults living with sickle cell disease who are considering whether to have a low-intensity stem cell transplant procedure that their lung health will not be compromised by the transplant.”

Until recently, bone marrow and blood stem cell transplants were the only cure for sickle cell disease, but relatively few adults have undergone the treatments due to health risks associated with high doses of chemotherapy required to prepare for transplants. In addition, the process requires a genetically well-matched donor, usually a sibling who does not have SCD. These procedures involve giving patients blood stem cells obtained from a donor to grow normal red blood cells to replace the “sickled” cells. The sickled cells block blood flow throughout the body, causing a host of problems, including episodes of acute pain, infections, stroke, and acute chest syndrome, in which lungs are deprived of oxygen.

Researchers say at least one-third of the sickle cell stem cell transplants performed are low-intensity. While they are slightly less effective than the standard transplants, adults who often have more pre-existing organ damage than children tend to do better with them and also experience a lower risk for complications such as graft-versus-host disease. The current study examined if these transplants offered other benefits for adults with already vulnerable lungs.

For the research, Ruhl and her team studied 97 patients with sickle cell disease who underwent a low-intensity, or non-myeloablative, blood stem cell transplant between 2004-2019 at the NIH’s Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Participants were then followed for up to three years.

The researchers conducted a variety of pulmonary function tests, including forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV-1), which measures the amount of air exhaled in the first second after forced exhalation. Another was a lung diffusion test, or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which measures how much oxygen moves from the lungs to the blood when exhaling. They also conducted a six-minute walk distance test, which measured how far a patient could walk and their oxygen levels during a set time.

After three years, overall lung function among the patients remained stable. FEV-1 levels remained relatively unchanged post-transplant compared to pre-transplant, indicating that lung function did not worsen over time. Notably, DLCO levels and six-minute walk distance improved significantly following transplant.

Ruhl said that larger studies with longer follow-up periods and the inclusion of transplant data from other clinical centers, including those from patients who received a standard transplant, are still needed to put the current findings in context. In the meantime, she and her team will continue to follow the NIH patients and report on longer term outcomes at the five- and 10-year mark.

In December 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two genetic therapies that use patients’ own blood stem cells to treat SCD. Researchers hope that the techniques used in this study will also be used to evaluate lung function for other new genetic therapies.

This study was supported in part by the Divisions of Intramural Research at NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (project AI001150) and NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (projects HL006211-08 and HL006007-06 and grant 1U01HL156620-01).

About the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI): NHLBI is the global leader in conducting and supporting research in heart, lung, and blood diseases and sleep disorders that advances scientific knowledge, improves public health, and saves lives. For more information, visit www.nhlbi.nih.gov.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®