Reform delay causes dental decay. It’s time for a national deal to fund dental care

A Senate committee has investigated why so many Australians are missing out on dental care and made 35 recommendations for reform.

By far the most sweeping is the call for universal coverage for essential dental care. The committee also proposed a suite of measures to get more dental care to groups who are missing out, including those in rural areas.

The government has three months to respond. It should lay out a plan to gradually expand coverage, while putting guardrails in place to make sure care is effective, efficient and equitable.

Read more:

Expensive dental care worsens inequality. Is it time for a Medicare-style ‘Denticare’ scheme?

If Australians can’t pay, they miss out

The Senate committee report follows more than a dozen national inquiries and reports into dental care since 1998, many with similar findings.

Dental care was left out of Medicare from the start, due to opposition from dentists and concerns about cost.

Half a century later, Australia still funds oral health very differently to how we fund care for the rest of the body, with patients paying most of the cost themselves.

As a result, many people miss out on care. In 2022-23, 2.3 million Australians skipped or delayed necessary dental care because of the cost – 17.6% of people, up from 16.4% the year before.

People on lower incomes were much more likely to miss out. People living in the poorest areas are around three times as likely to wait more than two years between visits to the dentist, compared to people in the wealthiest areas. One in four report delaying care.

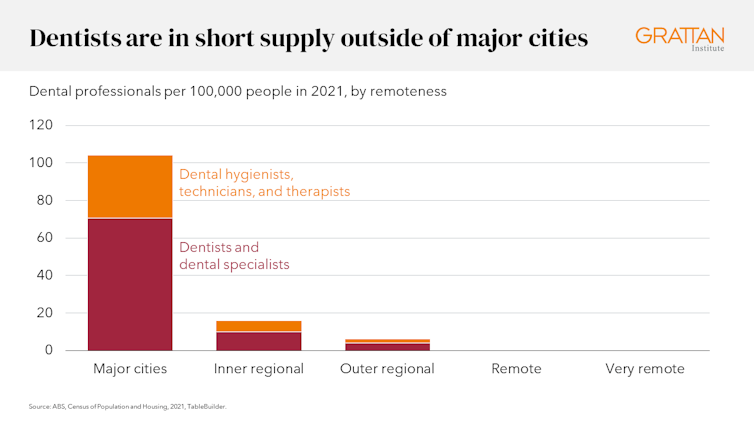

Even if you can afford to see a dentist, you might not be able to get in. Our analysis of census data shows there is one dentist for every 400 to 500 people in inner-city parts of most capital cities. But in Blacktown North in outer Sydney, there is only one dentist for every 5,100 people.

Regional areas fare even worse. There is only one for every 10,300 people in the northeast of Ballarat in Victoria. In some remote areas, there are no working dentists at all.

Grattan Institute

Missing dental care can affect the whole body

The consequences of missing dental care are serious. Around 80,000 hospital visits a year are for preventable dental conditions.

Oral health problems are also linked to a range of chronic diseases affecting the rest of the body too, and may cause damage to the brain.

On top of that, there are costs from people not being able to work or study, leading to further economic costs of more than half a billion dollars a year.

Those numbers only hint at the individual suffering involved. Dental disease often means pain, embarrassment and stigma.

The Senate inquiry heard from one 30-year-old on a low income who couldn’t afford dental care for years. They skipped meals for months to save up enough money to go to the dentist, and were finally diagnosed with advanced gum disease. They now expect to lose teeth, which will affect them for the rest of their life.

Dental problems are rising, spending is falling

Compared to five years ago, more of us have untreated dental decay, are concerned about the appearance of our teeth, avoid food due to dental problems, and have toothaches.

Despite all this, government spending on dental health has been falling. In the ten years to 2020-21, the federal government’s share of spending on dental services – excluding premium rebates – fell from 12% to 5%, while the states’ share fell from 10% to 9%.

Federal government spending on private health insurance rebates for dental care increased, but that doesn’t close the funding gap, and it doesn’t help the most vulnerable.

skynesher/Getty Images

Time for universal dental care

Most submissions to the Senate inquiry supported major reform to expand coverage for dental care, as previous reviews, Royal Commissions and a 2019 Grattan Institute report have recommended.

Getting there will be costly.

Read more:

Worried about your child’s teeth? Focus on these 3 things

The May budget kicked the can down the road by extending the current, inadequate funding for public dental services for another year. That funding will now stop in mid-2025, the same time that federal and state governments need to agree on a new National Health Reform Agreement – the biggest financial health deal in Australia.

With national health funding up in the air, there is an opportunity to finally work out a plan to expand dental coverage, starting in less than two years.

Phasing, fairness and efficiency will be key

Building a new, universal health care system is something Australia hasn’t done for generations. It will take more than simply expanding funding. Instead, governments should seize an historic opportunity to avoid the problems in other universal coverage schemes.

First, dental coverage should ramp up gradually. The Senate committee recommended phasing in a universal scheme, and mentioned establishing a Seniors Dental Benefit Scheme, and expanding the Child Dental Benefits Schedule to cover all children over time.

Starting with these steps would allow time for the workforce, providers, and government funding to expand to care for more people, as Australia builds a universal scheme.

Second, policies should ensure care is available where it’s needed most. This means getting more dentists in disadvantaged and rural areas.

kerriekerr/Getty Images

Even with more funding and broader coverage, some areas will struggle to attract dentists, particularly where there is a small population, few people who can afford fees and where clinics need to be set up from scratch.

The committee proposed incentives for providers in rural areas, new dental schools in regional universities, expanding rural medical student subsidies to dentistry and oral health, and better pay for clinicians in public dental clinics.

Third, given the huge costs involved, care must be efficient and effective. The committee outlined some ways to get good value for money. It said the universal scheme should fund essential oral health care, which would exclude cosmetic dentistry, for example. And it wants regulations and funding changed so oral health therapists can do more.

Read more:

Collaborating with communities delivers better oral health for Indigenous kids in rural Australia

Governments and the public should also be able to see where the billions of dollars of new investment are going, and the difference it is making.

Participating public and private clinics should record the treatments they provide, how satisfied their patients are, wait times and their results. And clinics should commit to following evidence-based guidelines and using data to continually improve their care.

Successive governments have skimped on dental care even as demand has risen. But those savings are a false economy that causes unnecessary disease and entrenches inequality. Today’s proposal for an overhaul should be the last – it’s time to fill this gap in the health system.