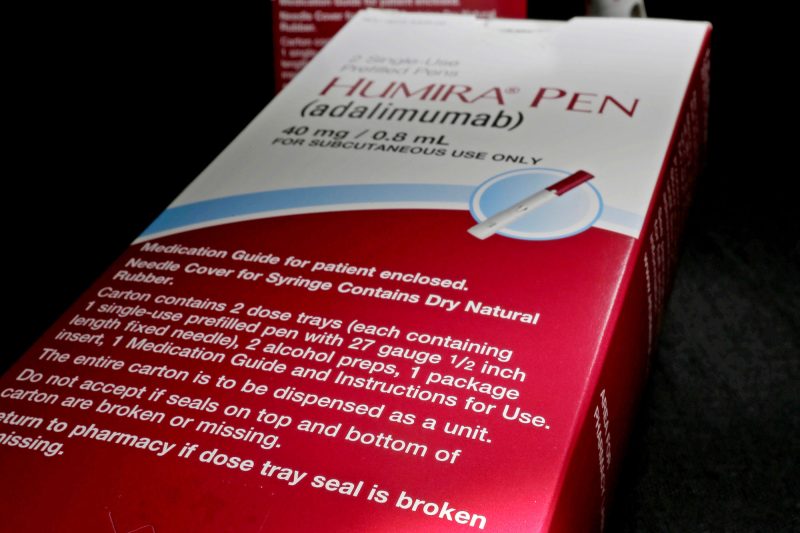

Save Billions or Stick With Humira? Drug Brokers Steer Americans to the Costly Choice

Tennessee last year spent $48 million on a single drug, Humira — about $62,000 for each of the 775 patients who were covered by its employee health insurance program and receiving the treatment. So when nine Humira knockoffs, known as biosimilars, hit the market for as little as $995 a month, the opportunity for savings appeared ample and immediate.

But it isn’t here yet. Makers of biosimilars must still work within a health care system in which basic economics rarely seems to hold sway.

For real competition to take hold, the big pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, the companies that negotiate prices and set the prescription drug menu for 80% of insured patients in the United States, would have to position the new drugs favorably in health plans.

They haven’t, though the logic for doing so seems plain.

Humira has enjoyed high-priced U.S. exclusivity for 20 years. Its challengers could save the health care system $9 billion and herald savings from the whole class of drugs called biosimilars — a windfall akin to the hundreds of billions saved each year through the purchase of generic drugs.

The biosimilars work the same way as Humira, an injectable treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. And countries such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Poland have moved more than 90% of their Humira patients to the rival drugs since they launched in Europe in 2018. Kaiser Permanente, which oversees medical care for 12 million people in eight U.S. states, switched most of its patients to a biosimilar in February and expects to save $300 million this year alone.

Biologics — both the brand-name drugs and their imitators, or biosimilars — are made with living cells, such as yeast or bacteria. With dozens of biologics nearing the end of their patent protection in the next two decades, biosimilars could generate much higher savings than generics, said Paul Holmes, a partner at Williams Barber Morel who works with self-insured health plans. That’s because biologics are much more expensive than pills and other formulations made through simpler chemical processes.

For example, after the first generics for the blockbuster anti-reflux drug Nexium hit the market in 2015, they cost around $10 a month, compared with Nexium’s $100 price tag. Coherus BioSciences launched its Humira biosimilar, Yusimry, in July at $995 per two-syringe carton, compared with Humira’s $6,600 list price for a nearly identical product.

“The percentage savings might be similar, but the total dollar savings are much bigger,” Holmes said, “as long as the plan sponsors, the employers, realize the opportunity.”

That’s a big if.

While a manufacturer may need to spend a few million dollars to get a generic pill ready to market, makers of biosimilars say their development can require up to eight years and $200 million. The business won’t work unless they gain significant market share, they say.

The biggest hitch seems to be the PBMs. Express Scripts and Optum Rx, two of the three giant PBMs, have put biosimilars on their formularies, but at the same price as Humira. That gives doctors and patients little incentive to switch. So Humira remains dominant for now.

“We’re not seeing a lot of takeup of the biosimilar,” said Keith Athow, pharmacy director for Tennessee’s group insurance program, which covers 292,000 state and local employees and their dependents.

The ongoing saga of Humira — its peculiar appeal to drug middlemen and insurers, the patients who’ve benefited, the patients who’ve suffered as its list price jumped sixfold since 2003 — exemplifies the convoluted U.S. health care system, whose prescription drug coverage can be spotty and expenditures far more unequal than in other advanced economies.

Biologics like Humira occupy a growing share of U.S. health care spending, with their costs increasing 12.5% annually over the past five years. The drugs are increasingly important in treating cancers and autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, that afflict about 1 in 10 Americans.

Humira’s $200 billion in global sales make it the best-selling drug in history. Its manufacturer, AbbVie, has aggressively defended the drug, filing more than 240 patents and deploying legal threats and tweaks to the product to keep patent protections and competitors at bay.

The company’s fight for Humira didn’t stop when the biosimilars finally appeared. The drugmaker has told investors it doesn’t expect to lose much market share through 2024. “We are competing very effectively with the various biosimilar offerings,” AbbVie CEO Richard Gonzalez said during an earnings call.

How AbbVie Maintains Market Share

One of AbbVie’s strategies was to warn health plans that if they recommended biosimilars over Humira they would lose rebates on purchases of Skyrizi and Rinvoq, two drugs with no generic imitators that are each listed at about $120,000 a year, according to PBM officials. In other words, dropping one AbbVie drug would lead to higher costs for others.

Industry sources also say the PBMs persuaded AbbVie to increase its Humira rebates — the end-of-the-year payments, based on total use of the drug, which are mostly passed along by the PBMs to the health plan sponsors. Although rebate numbers are kept secret and vary widely, some reportedly jumped this year by 40% to 60% of the drug’s list price.

The leading PBMs — Express Scripts, Optum, and CVS Caremark — are powerful players, each part of a giant health conglomerate that includes a leading insurer, specialty pharmacies, doctors’ offices, and other businesses, some of them based overseas for tax advantages.

Yet challenges to PBM practices are mounting. The Federal Trade Commission began a major probe of the companies last year. Kroger canceled its pharmacy contract with Express Scripts last fall, saying it had no bargaining power in the arrangement, and, on Aug. 17, the insurer Blue Shield of California announced it was severing most of its business with CVS Caremark for similar reasons.

Critics of the top PBMs see the Humira biosimilars as a potential turning point for the secretive business processes that have contributed to stunningly high drug prices.

Although list prices for Humira are many times higher than those of the new biosimilars, discounts and rebates offered by AbbVie make its drug more competitive. But even if health plans were paying only, say, half of the net amount they pay for Humira now — and if several biosimilar makers charged as little as a sixth of the gross price — the costs could fall by around $30,000 a year per patient, said Greg Baker, CEO of AffirmedRx, a smaller PBM that is challenging the big companies.

Multiplied by the 313,000 patients currently prescribed Humira, that comes to about $9 billion in annual savings — a not inconsequential 1.4% of total national spending on pharmaceuticals in 2022.

The launch of the biosimilar Yusimry, which is being sold through Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs pharmacy and elsewhere, “should send off alarms to the employers,” said Juliana Reed, executive director of the Biosimilars Forum, an industry group. “They are going to ask, ‘Time out, why are you charging me 85% more, Mr. PBM, than what Mark Cuban is offering? What is going on in this system?’”

Cheaper drugs could make it easier for patients to pay for their drugs and presumably make them healthier. A KFF survey in 2022 found that nearly a fifth of adults reported not filling a prescription because of the cost. Reports of Humira patients quitting the drug for its cost are rife.

Convenience, Inertia, and Fear

When Sue Lee of suburban Louisville, Kentucky, retired as an insurance claims reviewer and went on Medicare in 2017, she learned that her monthly copay for Humira, which she took to treat painful plaque psoriasis, was rising from $60 to $8,000 a year.

It was a particularly bitter experience for Lee, now 81, because AbbVie had paid her for the previous three years to proselytize for the drug by chatting up dermatology nurses at fancy AbbVie-sponsored dinners. Casting about for a way to stay on the drug, Lee asked the company for help, but her income at the time was too high to qualify her for its assistance program.

“They were done with me,” she said. Lee went off the drug, and within a few weeks the psoriasis came back with a vengeance. Sores covered her calves, torso, and even the tips of her ears. Months later she got relief by entering a clinical trial for another drug.

Health plans are motivated to keep Humira as a preferred choice out of convenience, inertia, and fear. While such data is secret, one Midwestern firm with 2,500 employees told KFF Health News that AbbVie had effectively lowered Humira’s net cost to the company by 40% after July 1, the day most of the biosimilars launched.

One of the top three PBMs, CVS Caremark, announced in August that it was creating a partnership with drugmaker Sandoz to market its own cut-rate version of Humira, called Hyrimoz, in 2024. But Caremark didn’t appear to be fully embracing even its own biosimilar. Officials from the PBM notified customers that Hyrimoz will be on the same tier as Humira to “maximize rebates” from AbbVie, Tennessee’s Athow said.

Most of the rebates are passed along to health plans, the PBMs say. But if the state of Tennessee received a check for, say, $20 million at the end of last year, it was merely getting back some of the $48 million it already spent.

“It’s a devil’s bargain,” said Michael Thompson, president and CEO of the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions. “The happiest day of a benefit executive’s year is walking into the CFO’s office with a several-million-dollar check and saying, ‘Look what I got you!’”

Executives from the leading PBMs have said their clients prefer high-priced, high-rebate drugs, but that’s not the whole story. Some of the fees and other payments that PBMs, distributors, consultants, and wholesalers earn are calculated based on a drug’s price, which gives them equally misplaced incentives, said Antonio Ciaccia, CEO of 46Brooklyn, a nonprofit that researches the drug supply chain.

“The large intermediaries are wedded to inflated sticker prices,” said Ciaccia.

AbbVie has warned some PBMs that if Humira isn’t offered on the same tier as biosimilars it will stop paying rebates for the drug, according to Alex Jung, a forensic accountant who consults with the Midwest Business Group on Health.

AbbVie did not respond to requests for comment.

One of the low-cost Humira biosimilars, Organon’s Hadlima, has made it onto several formularies, the ranked lists of drugs that health plans offer patients, since launching in February, but “access alone does not guarantee success” and doesn’t mean patients will get the product, Kevin Ali, Organon’s CEO, said in an earnings call in August.

If the biosimilars are priced no lower than Humira on health plan formularies, rheumatologists will lack an incentive to prescribe them. When PBMs put drugs on the same “tier” on a formulary, the patient’s copay is generally the same.

In an emailed statement, Optum Rx said that by adding several biosimilars to its formularies at the same price as Humira, “we are fostering competition while ensuring the broadest possible choice and access for those we serve.”

Switching a patient involves administrative costs for the patient, health plan, pharmacy, and doctor, said Marcus Snow, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

Doctors’ Inertia Is Powerful

Doctors seem reluctant to move patients off Humira. After years of struggling with insurance, the biggest concern of the patient and the rheumatologist, Snow said, is “forced switching by the insurer. If the patient is doing well, any change is concerning to them.” Still, the American College of Rheumatology recently distributed a video informing patients of the availability of biosimilars, and “the data is there that there’s virtually no difference,” Snow said. “We know the cost of health care is exploding. But at the same time, my job is to make my patient better. That trumps everything.”

“All things being equal, I like to keep the patient on the same drug,” said Madelaine Feldman, a New Orleans rheumatologist.

Gastrointestinal specialists, who often prescribe Humira for inflammatory bowel disease, seem similarly conflicted. American Gastroenterological Association spokesperson Rachel Shubert said the group’s policy guidance “opposes nonmedical switching” by an insurer, unless the decision is shared by provider and patient. But Siddharth Singh, chair of the group’s clinical guidelines committee, said he would not hesitate to switch a new patient to a biosimilar, although “these decisions are largely insurance-driven.”

HealthTrust, a company that procures drugs for about 2 million people, has had only five patients switch from Humira this year, said Cora Opsahl, director of the Service Employees International Union’s 32BJ Health Fund, a New York state plan that procures drugs through HealthTrust.

But the biosimilar companies hope to slowly gain market footholds. Companies like Coherus will have a niche and “they might be on the front end of a wave,” said Ciaccia, given employers’ growing demands for change in the system.

The $2,000 out-of-pocket cap on Medicare drug spending that goes into effect in 2025 under the Inflation Reduction Act could spur more interest in biosimilars. With insurers on the hook for more of a drug’s cost, they should be looking for cheaper options.

For Kaiser Permanente, the move to biosimilars was obvious once the company determined they were safe and effective, said Mary Beth Lang, KP’s chief pharmacy officer. The first Humira biosimilar, Amjevita, was 55% cheaper than the original drug, and she indicated that KP was paying even less since more drastically discounted biosimilars launched. Switched patients pay less for their medication than before, she said, and very few have tried to get back on Humira.

Prescryptive, a small PBM that promises transparent policies, switched 100% of its patients after most of the other biosimilars entered the market July 1 “with absolutely no interruption of therapy, no complaints, and no changes,” said Rich Lieblich, the company’s vice president for clinical services and industry relations.

AbbVie declined to respond to him with a competitive price, he said.